There’s an innovative scheme to marry up English language students in the UK with low-skill vacancies, says Melanie Butler

Bournemouth, and neighbouring Christchurch and Poole in the south of England, combined to make up one of the UK’s oldest and most popular language-travel destinations. Devastated by the twin effects of Covid and Brexit, they have received special funding from their local authority to help them keep the region at the top of the English language charts.

The main stumbling block to the revival of British language travel, especially from long- haul regions like Asia, is the lack of work rights for language students. At the same time, all along the coast of southern England, the local hospitality industry is facing a severe shortage of workers caused, in part, by the number of EU workers who went home during Covid.

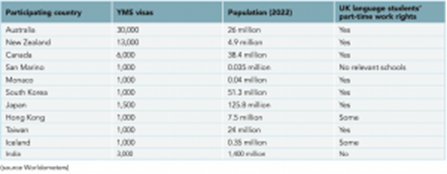

There is an existing and growing source of young foreign workers, Britain’s Youth Mobility Scheme Project, which offers 18 to 30-year-olds from 11 countries the right to live and work in the UK for up to two years with reciprocal rights for young Britons travelling in the other direction.

Three of these are English-speaking countries and they’re entitled to 83% of the total number of Youth Mobility visas on offer, but numbers from these countries have been falling in recent years. At the same time, the demand from the Asian countries has been growing so fast that the UK Government has to run a ballot to choose who comes.

The problem for the hospitality industry is that Asians coming on ‘working holidays’ often have a low level of English, so the answer was to link up with local language schools. Members of the local International Education Association (IEA), which represents language schools and colleges in the area, together with the Bournemouth Area Hospitality Association (BAHA), are the ones who came up with the innovative solution of Youth Mobility Scheme visas.

“It will breathe fresh life into the beleaguered hospitality and English language sectors,” says project co-ordinator Michele Medhurst, “while providing travel, work and study opportunities for young people in this vibrant location.”

It works like this: anyone with a Youth Mobility Scheme visa can apply to the Bournemouth scheme. If English is not their first language they must take an online English test. If they score at B1 level or above they’ll be placed in a paid job and given free professional training.

Those below B1 will be offered a place on an English course for which they pay, but they’re guaranteed a job at the end of the course.

This bold initiative begs the question: why can’t the Government increase the number of visas of the Youth Mobility Scheme in the existing Asian partner countries for young people who agree to pay for an English course and to take work in high-needs low-skill areas such hospitality and childcare?

Currently, the UK Youth Mobility scheme is skewed not only in favour of English speakers but in favour of white people, as white majority countries are allocated 87% of all the visas.

Our table shows that the tiny European states are allocated the same number of Youth Mobility visas as much larger Asian countries: San Marino, population 34,000. and South Korea, population 51.3 million are allocated 1,000 visas each. So every year the UK is willing to grant one visa for every 34 people in San Marino, but the figure for South Korea is one per 51,300.

And as for the argument that the restrictions on the numbers are set as part of trade deals, the final column on our table suggests this reciprocity does not exist for language students. Britons who go to these countries to study the language are allowed to work part-time in nearly all of them. Why not return the favour?

Youth Mobility Scheme visa allocation